Imagine writing a story not with ink, but with hot wax and vibrant dyes. This is the essence of Batik print, a mesmerizing textile art that transforms simple cloth into a canvas of intricate patterns and rich colors. From the royal courts of Java to the bustling artisan workshops of India, Batik is a craft that has crossed oceans and centuries, carrying with it a legacy of patience, precision, and profound cultural meaning.

In this post, we will immerse ourselves in the world of wax-resist dyeing. We will trace the journey of Batik from its Indonesian roots to its unique adaptations in India, uncover the secrets of the tjanting tool, and learn how this ancient technique continues to inspire modern fashion and art lovers today.

The Origins: A Journey Across Oceans

The term "Batik" is derived from the Javanese words amba (to write) and titik (dot). This literal translation—"to write with dots"—perfectly captures the meticulous nature of the craft. While the exact origins of wax-resist dyeing are debated, with evidence of similar techniques found in Egypt and China, it was on the island of Java in Indonesia that Batik reached its pinnacle of artistic expression.

UNESCO designated Indonesian Batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, recognizing its deep cultural roots. However, the art form also found a welcoming home in India. Trade routes brought the technique to Indian shores, where it flourished in regions like Shantiniketan in West Bengal, Mundra in Gujarat, and prominently in Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh. Today, traditional Indian prints created using the Batik method have developed their own distinct identity, blending local motifs with the classic wax-resist technique.

The Science of Resistance: How Batik Works

At the heart of Batik is a simple yet brilliant principle: oil and water don't mix. In this case, wax acts as a shield. When melted wax is applied to fabric, it permeates the fibers and hardens. When the fabric is subsequently dipped in dye, the waxed areas resist the color, remaining the original color of the cloth.

This process allows for the creation of incredibly complex, multi-colored designs. By repeating the waxing and dyeing process—applying wax to preserve the first color, then dyeing in a darker shade, and so on—artisans can build layers of color and pattern. The result is a depth and richness that surface printing simply cannot match.

Tools of the Trade: The Tjanting and The Tjap

The creation of authentic Indonesian textile art and Indian Batik relies on specific, traditional tools that have remained largely unchanged for generations.

The Tjanting (Canting)

The tjanting is a pen-like instrument with a small copper reservoir for holding hot wax and a fine spout for drawing. It is the tool of the master artist. With a steady hand, the artisan "draws" flowing lines, intricate dots, and detailed motifs directly onto the fabric. This tool allows for the high level of detail and organic, free-flowing lines that are characteristic of hand-drawn Batik (known as Batik Tulis).

The Tjap (Cap)

For larger, repeating patterns, artisans use the tjap, a copper stamp. The stamp is dipped into a pan of hot wax and pressed onto the fabric. This method is faster and allows for more uniform designs, often used for creating borders or geometric backgrounds.

The Wax Blend

The wax itself is a crucial component. It is typically a blend of beeswax and paraffin wax. Beeswax is pliable and adheres well to the fabric, while paraffin is brittle. The "crackle" effect—fine veins of color running through the resisted areas—is a signature look of many Batik styles. This happens when the paraffin wax cracks during the dyeing or handling process, allowing tiny amounts of dye to seep in.

The Creative Process: Step-by-Step

Creating a piece of Batik print fabric is a labor-intensive process that requires patience and foresight.

- Preparation: The fabric (usually cotton or silk) is washed and soaked to remove starches and impurities, ensuring it can absorb the dye and wax evenly.

- Waxing: The artist applies the hot wax design using a tjanting or tjap. This is the most critical step; a mistake here is difficult to correct.

- First Dyeing: The fabric is immersed in the lightest color dye. The waxed areas remain white (or the original fabric color).

- Second Waxing: Once dry, new layers of wax are applied to cover areas that the artist wants to keep in the first dye color.

- Subsequent Dyeing: The fabric is dipped in a darker dye. This process of waxing and dyeing can be repeated multiple times for complex, multi-colored designs.

- Dewaxing: Finally, the fabric is boiled in water to melt off the wax, revealing the stunning, multi-layered design beneath.

Motifs and Meanings: A Cultural Language

Batik patterns are rarely just decorative; they are symbolic. In traditional contexts, specific motifs were reserved for royalty or special occasions.

- Parang (The Knife/Dagger): One of the most famous Javanese patterns, depicting a diagonal S-shape. It symbolizes power and strength and was historically reserved for kings and rulers.

- Kawung: A geometric pattern resembling the cross-section of a palm fruit. It represents purity and honesty.

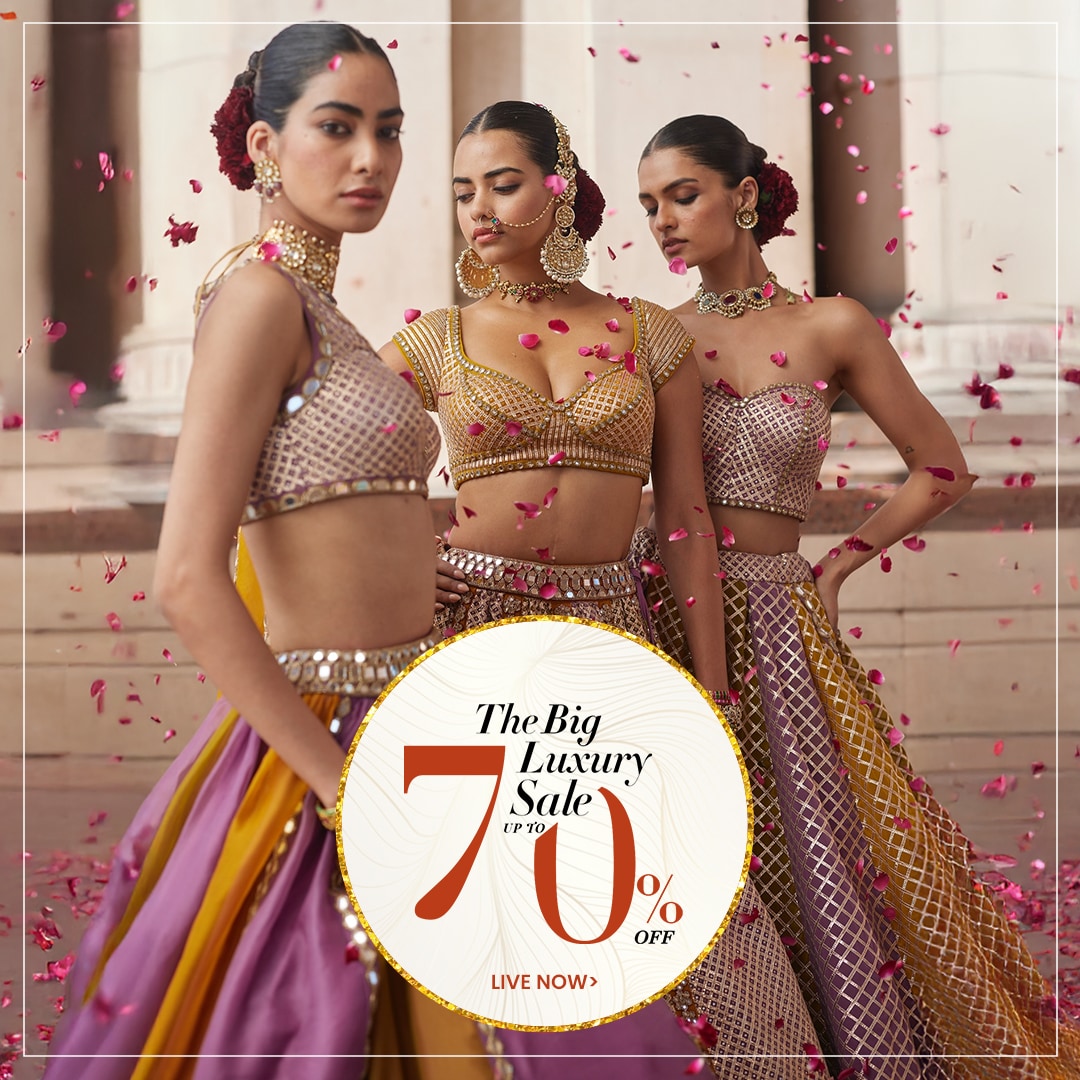

- Flora and Fauna: In Indian Batik, particularly from Ujjain and Gujarat, you will often find motifs inspired by nature—creepers, flowers, and birds—blended with traditional Indian geometric borders.

- Sawat (Wings): Represents the wings of the mythical bird Garuda, symbolizing the connection to the divine.

Batik in the Modern World

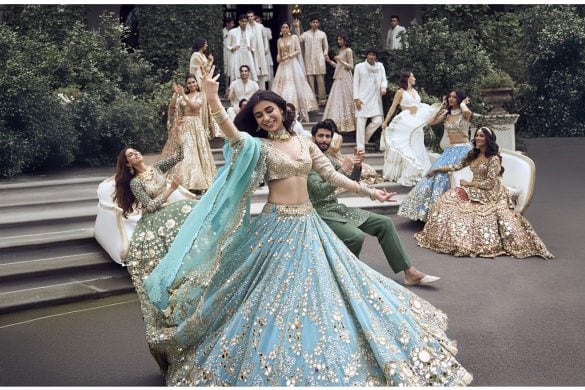

While deeply rooted in history, Batik print is far from a relic. It has seamlessly transitioned into modern fashion and decor. Contemporary designers are reimagining Batik, moving beyond traditional sarongs to create chic dresses, shirts, scarves, and even home accessories like wall hangings and cushion covers.

The "perfect imperfection" of Batik—the slight variations in line width, the accidental drips, and the signature crackle effect—is what makes it so prized in an era of mass-produced uniformity. Each piece tells the story of the human hand that made it.

Preserving a Global Heritage

Whether it is a classic Javanese masterpiece or a vibrant creation from the artisans of Ujjain, Batik print represents a universal language of art. It bridges cultures through the shared medium of wax and dye.

Owning a piece of Batik is about appreciating the slow, meditative process of its creation. It is a celebration of wax-resist dyeing, a technique that turns simple cloth into a canvas of cultural history. As we embrace sustainable and artisanal fashion, the timeless allure of Batik continues to shine, proving that some traditions are too beautiful to fade.